Gobekli Tepe, found in Turkey, is a remarkable site that challenges the traditional beliefs about the dawn of civilization. Its age predates Stonehenge by 6,000 years, making it a fascinating location to explore.

The hilltop location, previously believed to be a medieval cemetery, has now been recognized as an important prehistoric worship site. Klaus Schmidt’s discovery of large carved stones, dating back 11,000 years ago, was found in the ancient city of Urfa in southeastern Turkey. The megaliths were created by prehistoric people without the use of metal tools or pottery and are older than Stonehenge by 6,000 years. Schmidt, a German archaeologist who has been studying the area for over a decade, is convinced that Gobekli Tepe is the world’s oldest temple.

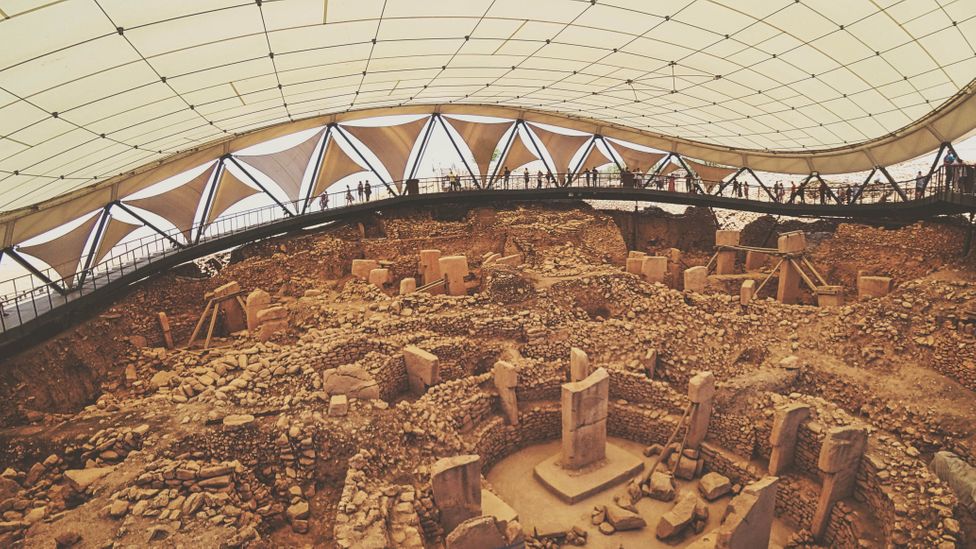

At the crack of dawn, my ride arrives at my hotel in Urfa and greets me with a cheerful “Good morning.” We drive for half an hour until we reach a grassy hill where we park beside some barbed wire. A group of workers leads us up to a collection of rectangular pits shaded by a steel roof, which is the main site of excavation. Within the pits, circles of standing stones or pillars are arranged, while four other rings of partially unearthed pillars can be seen on the nearby hill. Each ring has a similar layout: two large T-shaped pillars made of stone occupy the center, surrounded by slightly smaller stones facing inward. The tallest pillars are about 16 feet high and weigh between seven and ten tons. As we walk amid the pillars, some are unadorned, while others are intricately carved with images of foxes, lions, scorpions, and vultures crawling and twisting along their broad surfaces.

As we look at the Map of Gobekli Tepe Guilbert Gates, Schmidt draws our attention to a remarkable sight – the massive stone rings, with one of them measuring an impressive 65 feet in diameter. Schmidt tells us that this was the first ever sacred place built by humans. We are standing atop a height of 1,000 feet, and the view stretches out to the horizon in all directions. Schmidt urges us to picture what this land would have been like 11,000 years ago, before it was transformed by extensive settlement and farming which has turned it into a barren and monotonous brown landscape we see today.

Ancient individuals were able to witness stunning herds of wildlife, including gazelles and other animals, as well as serene flowing rivers that enticed geese and ducks during migratory periods. They also had access to an abundance of fruit and nut trees, and lush fields of wild wheat and barley varieties, such as emmer and einkorn. According to Schmidt, a member of the German Archaeological Institute, this location was a true paradise. Gobekli Tepe is situated on the northern border of the Fertile Crescent, a region with a mild climate and fertile land stretching from the Persian Gulf to present-day Egypt, Israel, Jordan, and Lebanon. Due to these desirable conditions, hunter-gatherers from Africa and the Levant would have been drawn to the area. Since there is no evidence of permanent residency on the summit of Gobekli Tepe, Schmidt believes that this site served as a place of worship on an unprecedented scale, humanity’s first “cathedral on a hill.”

As the sun gets higher in the sky, Schmidt puts on a white scarf in a turban-style and carefully walks down the hill among the ancient objects. He speaks quickly in German, sharing that he has used advanced technology like ground-penetrating radar and geomagnetic surveys to map the entire summit. Schmidt has identified at least 16 other megalith rings that are still buried across 22 acres. The current excavation only covers one acre, which is less than 5 percent of the site. According to him, archaeologists could continue to dig here for the next 50 years and still not uncover everything that lies beneath the surface.

Back in the 1960s, Gobekli Tepe was examined by anthropologists from the University of Chicago and Istanbul University, but they dismissed it as just an abandoned medieval cemetery upon seeing broken limestone slabs. It wasn’t until 1994 when Schmidt decided to personally visit the hill during his own survey of prehistoric sites in the area after reading a brief mention of it in the University of Chicago researchers’ report. Schmidt knew right away that the place was exceptional upon his first sight of it.

Gobekli Tepe, which translates to “belly hill” in Turkish, has a unique shape compared to the nearby plateaus. It boasts a gently rounded top that stands 50 feet above the surrounding landscape. According to Schmidt, this distinct feature caught his attention and convinced him that only human beings could have built such a structure. Upon further inspection, the fragments of limestone that initial surveyors believed to be gravestones now held a new significance. This discovery revealed the existence of a monumental Stone Age site.

Upon his return with five companions a year later, Schmidt and his team discovered the first megaliths, some of which were scarred by plows due to their proximity to the surface. As they dug deeper, they uncovered pillars arranged in circles, but found no signs of a settlement such as cooking hearths, houses, or trash pits, nor any clay fertility figurines that are common in neighboring sites from around the same time period. However, evidence of tool use was present, including stone hammers and blades that closely resembled those found at nearby sites previously carbon-dated to around 9000 B.C. Based on this, Schmidt and his team estimate that Gobekli Tepe’s stone structures are of the same age. Carbon dating done by Schmidt at the site confirms this conclusion.

Schmidt believes that the slanting terrain of Gobekli Tepe is perfect for stonecutting. Flint tools were likely used by prehistoric masons to carve out softer limestone protrusions, forming pillars on-site before hauling them a short distance up to the peak and standing them upright. Afterwards, according to Schmidt, the builders buried the stone rings with dirt. They then constructed another ring close by or on top of the previous one. The mound was formed over time through the accumulation of these layers.

Schmidt is currently in charge of a group consisting of more than 12 German archaeologists, 50 local workers, and a constant flow of eager students. He usually conducts excavations at the location for two months during the spring and two months during the fall since the summer heat often reaches 115 degrees, making it too hot to dig, while the winter season brings heavy rainfall. To serve as their main headquarters, he purchased a conventional Ottoman house in Urfa, a city with approximately half a million inhabitants, in 1995, complete with a courtyard.

During my visit to Gobekli Tepe, I meet a Belgian archaeozoologist named Joris Peters who is an expert in animal remains. He has analyzed over 100,000 bone fragments from the site and has discovered cut marks and splintered edges on many of them, suggesting that the animals were butchered and cooked. The bones are stored in plastic crates in a storeroom at the house and provide insight into how the people who created Gobekli Tepe lived. Peters has identified tens of thousands of gazelle bones, which make up over 60% of the total, as well as bones from other wild game like boar, sheep, and red deer. He also found bones from a dozen different bird species including vultures, cranes, ducks, and geese. Peters confirms that the site was a hunter-gatherer community as all the bones analyzed were from wild animals indicating that the people who lived there had not yet domesticated animals or farmed.

Peters and Schmidt suggest that the builders of Gobekli Tepe were about to experience a significant change in their way of life. This was due to the availability of raw materials for farming such as wild sheep and grains that could be domesticated. They also had people who had the potential to domesticate these resources. Studies conducted at other sites in the area reveal that within a thousand years of Gobekli Tepe’s construction, settlers had already started keeping sheep, cattle, and pigs. Researchers discovered evidence of the world’s earliest domesticated strains of wheat at a prehistoric village located only 20 miles away from Gobekli Tepe. Radiocarbon dating suggests that agriculture began to develop only five centuries after the construction of Gobekli Tepe, around 10,500 years ago.

According to recent discoveries, scholars may need to reexamine their theories about the development of civilization. Traditionally, it has been believed that people needed to settle down and cultivate crops before they could construct elaborate social structures and religious sites. However, experts like Schmidt now argue that the opposite is true: the construction of impressive stone monuments paved the way for the emergence of organized societies. The construction of these massive structures, as seen at Gobekli Tepe, could not have been accomplished by small groups of hunter-gatherers. Instead, hundreds of workers would have been required to carve and transport massive stone pillars, necessitating the establishment of permanent settlements. This new perspective suggests that sociocultural changes occurred prior to the advent of agriculture, contradicting previous beliefs that farming was a prerequisite for societal advancement. As such, experts like archaeologist Ian Hodder suggest that this region may be the true birthplace of complex Neolithic societies.

The mystery behind the stone rings built and buried by early people at Gobekli Tepe still remains unsolved. The culture and beliefs of these builders are too distant and foreign for us to comprehend, as they existed 6,000 years before the invention of writing. While archaeologists have their theories, the lack of evidence of human habitation near the site contradicts the idea of it being a settlement or gathering place. Pillar carvings dominated by menacing creatures like lions, spiders, snakes, and scorpions suggest that the hunters who built the complex may have been trying to master their fears. Vulture carvings, which are believed to represent the transportation of the dead up to the heavens, were also found in nearby sites from the same era, indicating a shared culture and beliefs. Despite the absence of sources to explain the meaning of symbols, the search for explanation continues to fuel the irresistible human urge to understand the unexplainable.

Vincent J. Musi’s photograph of a pillar with carvings that could potentially represent priestly dancers captures the mystery and intrigue surrounding Gobekli Tepe, an ancient complex that German archaeologist Klaus Schmidt believes has yet to reveal its secrets. Schmidt and his team have discovered fragments of human bone in the layers of dirt that cover the site, as well as hardened limestone floors beneath the rings. He hypothesizes that Gobekli Tepe could have served as a burial ground or center of a death cult, with the dead laid out among the gods and spirits of the afterlife. Schmidt suggests that the location of the complex was intentional, offering the deceased an ideal view of a hunter’s dream.

An entrance was discovered hidden beneath the surface of a temple floor, as seen in the photograph captured by Vincent J. Musi for the National Geographic Society.

The image depicts a lion that has been intricately carved into a section of a pillar. The craftsmanship is remarkable, and the lion’s features are captured with great detail. It is a stunning piece of art that exemplifies the skill and creativity of the carver.

A sign indicating the direction to Gobekli Tepe can be seen in a photograph captured by Vincent J. Musi for the National Geographic Society’s Corbis collection.